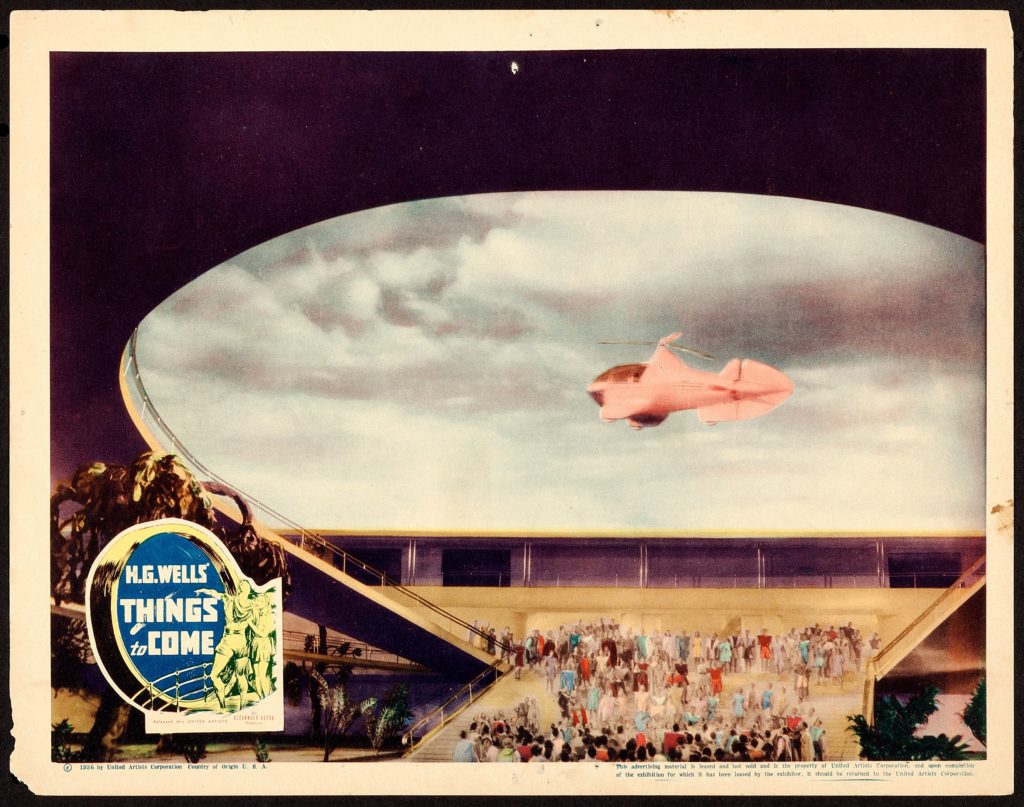

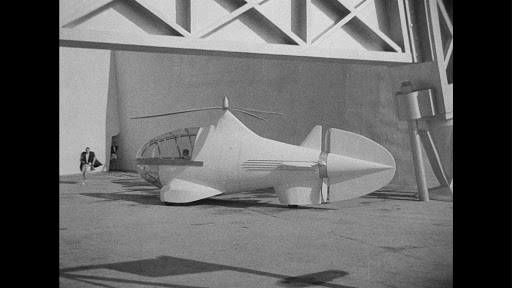

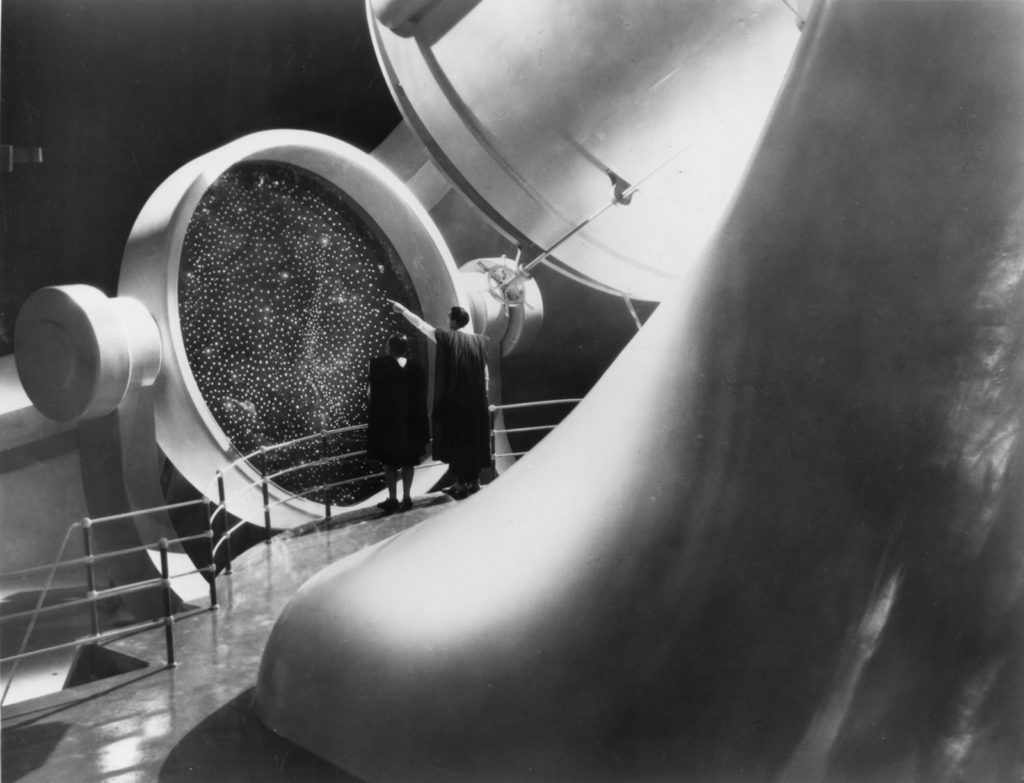

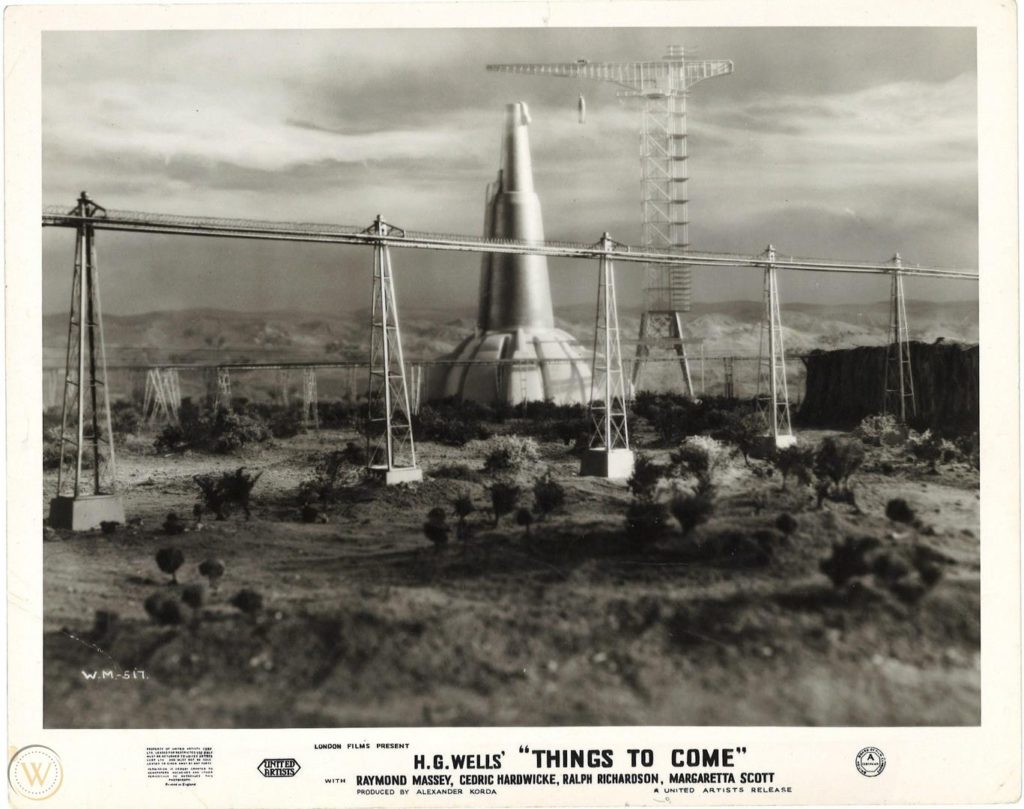

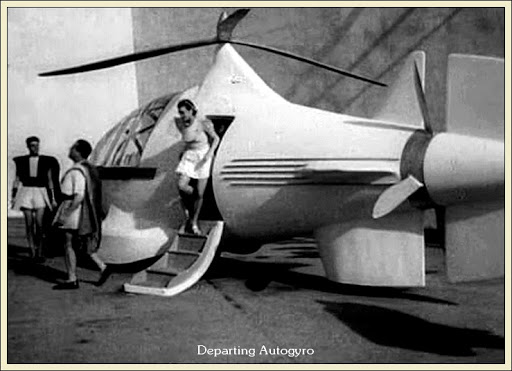

I recently watched THINGS TO COME on the Archive.org website and thoroughly enjoyed the journey into it’s retro future. Prompted from it being referenced in the Interplanetary podcast show recently, I researched two elements of the film – the art design (or production design) and the music. The plot lines investigated by HG Wells are so rich in depth that no matter how epic the special effects of the movie, an hour and a half can only give a quick nod to the themes and characters before moving on to the next part of the plot. Split in three, the first third references the build up to war (the movie was released in 1936), but the themes of the middle section and the downfall of humanity were more amusing than disastrous, given everyone’s ‘I say, are they the British?’ skills in received pronunciation. I was quite impressed of the strong female lead character given this was scripted in the 30’s. To be honest, all I wanted to see was the arrival of the ‘future’, the miniature sets and Deco style which I fully enjoyed. I read ‘The shape of things to come‘ a long time ago and it might be worth a reread at some point. Anyway, fully enjoyed this one – William Cameron Menzies and Arthur Bliss are legends.

William Cameron Menzies – Artistic Director

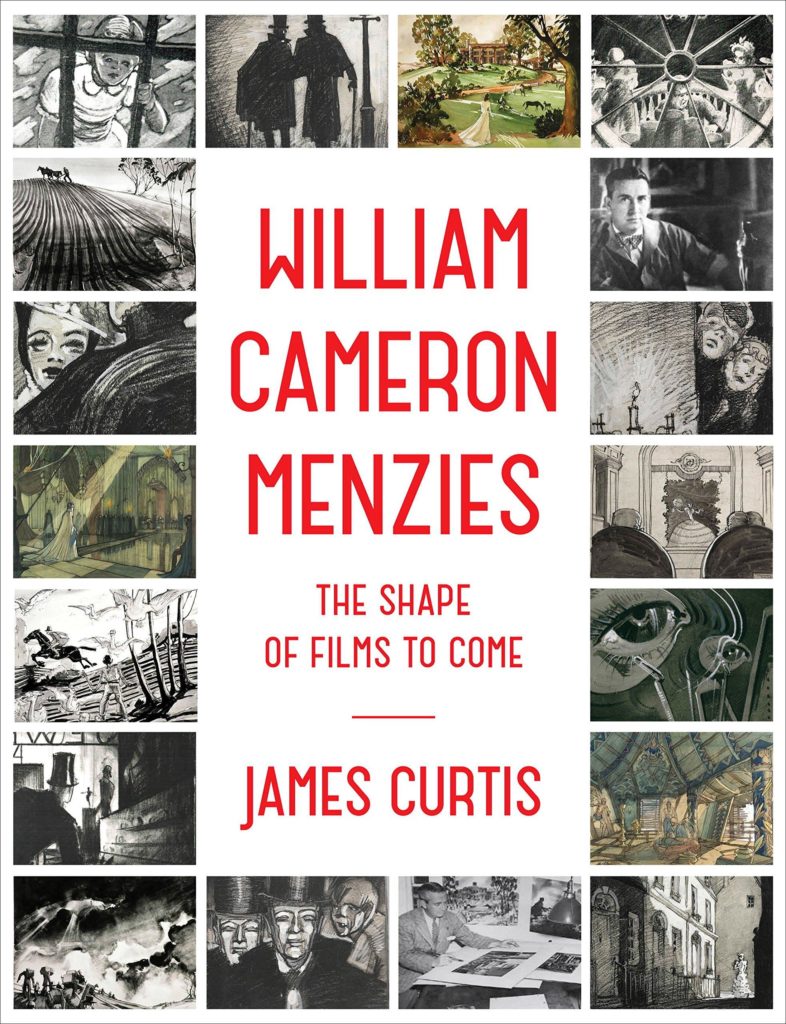

William Cameron Menzies (July 29, 1896 – March 5, 1957) was an American film production designer (a job title he invented) and art director as well as a film director and producer during a career spanning five decades. He earned acclaim for his work in silent film, and later pioneered the use of color in film for dramatic effect.

Menzies joined Famous Players-Lasky, later to evolve into Paramount Pictures, working in special effects and design. He quickly established himself in Hollywood with his elaborate settings for Robin Hood (1922), The Thief of Bagdad (1924), The Bat (1926), The Dove (1927), Sadie Thompson (1928), and Tempest (1928). In 1929, Menzies formed a partnership with producer Joseph M. Schenck to create a series of early sound short films visualizing great works of music, including a 10-minute version of Dukas’s The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, and created the production design and special effects for Schenck’s feature film The Lottery Bride (1930).

Menzies’s work on The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1938) prompted David O. Selznick to hire him for Gone with the Wind (1939). Selznick’s faith in Menzies was so great that he sent a memorandum to everyone at Selznick International Pictures who was involved in the production reminding them that “Menzies is the final word” on everything related to Technicolor, scenic design, set decoration, and the overall look of the production.

“Production designer” (which is sometimes used interchangeably with “art director”) was coined specifically for Menzies, to refer to his being the final word on the overall look of the production; it was intended to describe his ability to translate Selznick’s ideas to drawings and paintings from which he and his fellow directors worked.

Menzies was the director of the burning of Atlanta sequence in Gone with the Wind. He also re-shot the Salvador Dalí dream sequence of Alfred Hitchcock’s Spellbound (1945).

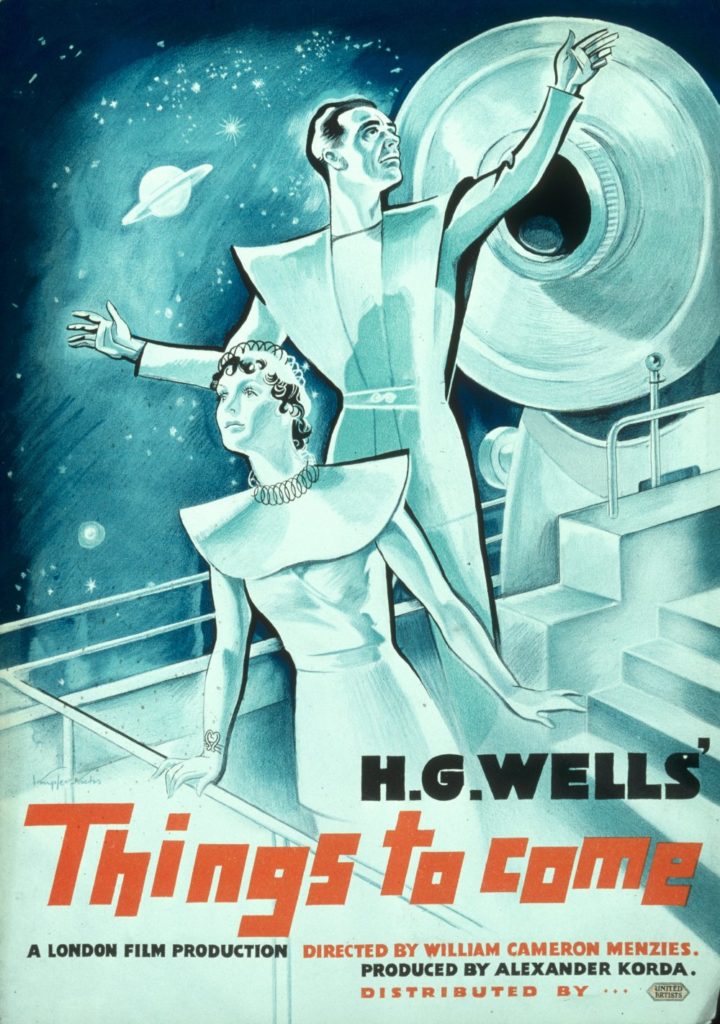

In addition, Menzies directed dramas and fantasy films. He made two science-fiction films: Things to Come (1936), based on H.G. Wells’ work for producer Alexander Korda which predicted war and technical advancement; and Invaders from Mars (1953), which mirrored many fears about aliens and outside threats to humanity in the 1950s.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Cameron_Menzies

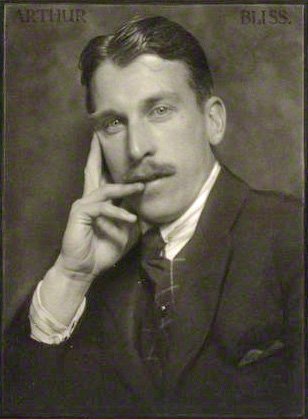

Arthur Bliss – Score

Sir Arthur Edward Drummond Bliss CH KCVO (2 August 1891 – 27 March 1975) was an English composer and conductor.

Bliss’s musical training was cut short by the First World War, in which he served with distinction in the army. In the post-war years he quickly became known as an unconventional and modernist composer, but within the decade he began to display a more traditional and romantic side in his music. In the 1920s and 1930s he composed extensively not only for the concert hall, but also for films and ballet.

In the Second World War, Bliss returned to England from the US to work for the BBC and became its director of music. After the war he resumed his work as a composer, and was appointed Master of the Queen’s Music.

In Bliss’s later years, his work was respected but was thought old-fashioned, and it was eclipsed by the music of younger colleagues such as William Walton and Benjamin Britten. Since his death, his compositions have been well represented in recordings, and many of his better-known works remain in the repertoire of British orchestras. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arthur_Bliss

Upon its release, critics praised one aspect of the production unreservedly: the score by the British modernist composer Arthur Bliss. In the heady early days of the creation of Things to Come, Wells himself contacted Bliss to supply music for his cinematic vision. Wells later wrote, “The music is a part of the constructive scheme of the film, and the composer, Mr. Arthur Bliss, was practically a collaborator in its production. . . . This Bliss music is not intended to be tacked on; it is part of the design.” Bliss, who had written an essay on film music as early as 1922, responded with alacrity to Wells’ ideas, producing a score that is considered to be one of the finest achievements by a British film composer, music on a level with scores by Vaughan Williams, Malcolm Arnold, and William Walton. In a prophetic anticipation of John Williams, Bliss concludes the suite drawn from his music for Things to Come with a broad Elgarian tune that hails Wells’ cloudless, technologically perfect future. Byron Adams is Professor of Musicology at the University of California, Riverside