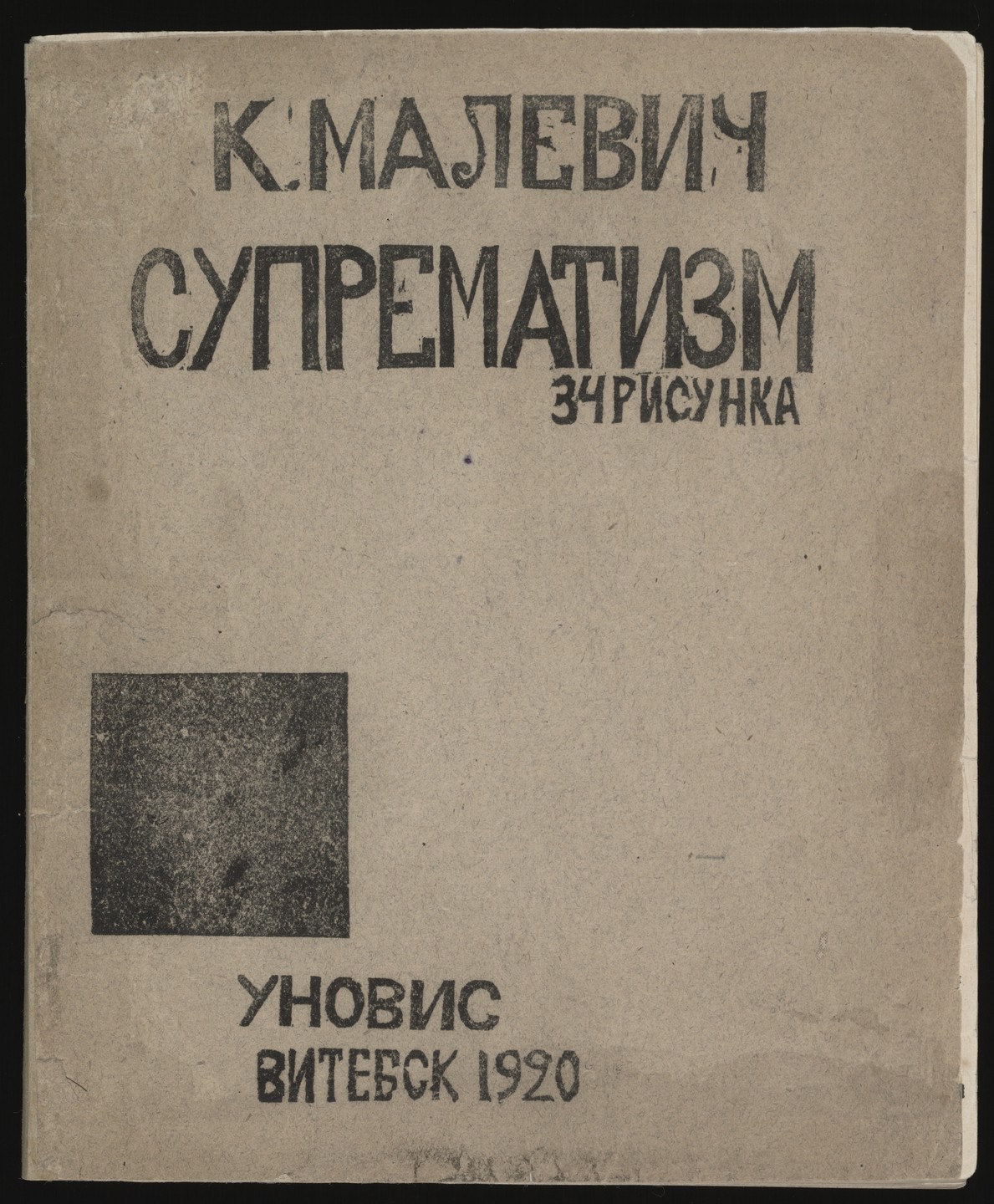

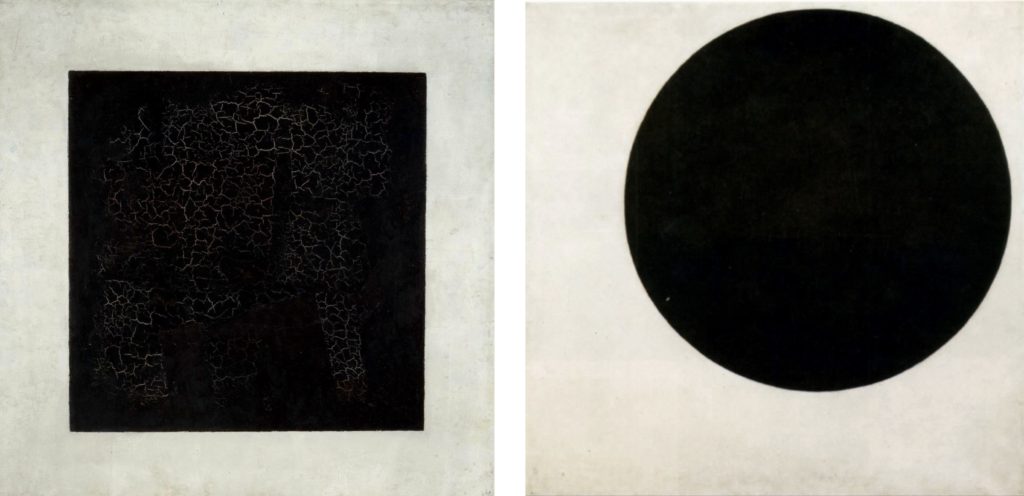

Suprematism 34 Drawings

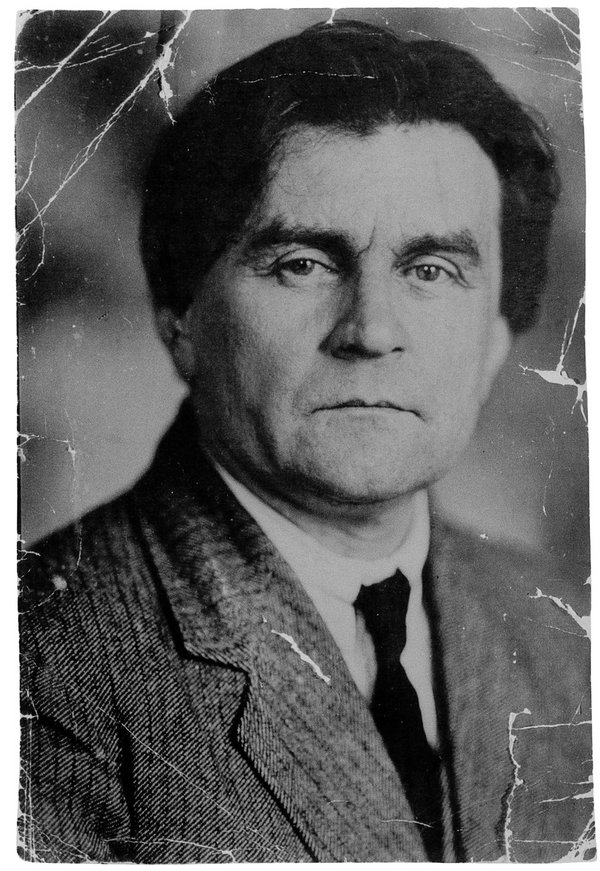

Kazimir Malevich and the use of the word ‘Sputnik’.

Kazimir Malevich’s work tells a compelling story about the dream of a new social order, the struggle of revolutionary ideals and the power of art itself. Central to this was his prescient fascination with outer space, the cosmos and man’s destiny to explore it (at one point he kept a telescope in his pocket), and a key part of his art pre-empted Russia’s enchantment with travel beyond our world.

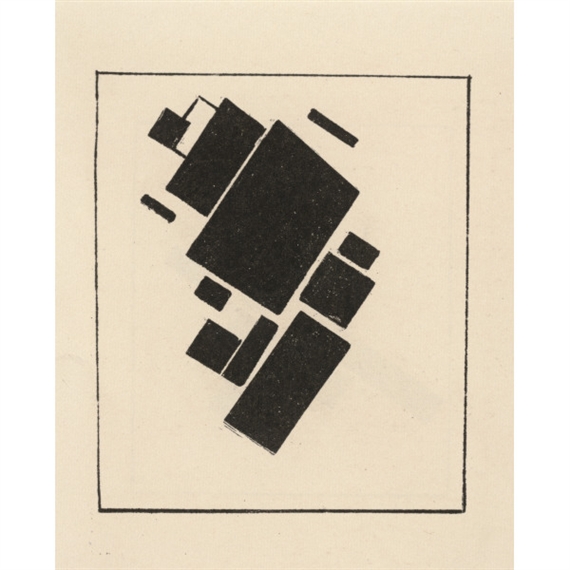

In Malevich’s everyday life, his proclamation of the inevitable break from earth and speculative mastery of space turned into a passionate immersion in astronomy. During his Vitebsk years (1919-22), he was never parted from his pocket telescope, constantly observing and studying the starry sky, the map of which he knew thoroughly. This engendered one of his most astounding texts, Suprematism: 34 Drawings, published on 15 December 1920 with its prophetic lines in the introduction about humanity’s cosmic future. It was here that he gave the ordinary word ‘sputnik’ – Russian for companion or fellow traveller – the meaning that made it famous. As we know, ‘sputnik’ has existed in all the world’s languages without translation ever since the call signs of an artificial, man-made celestial body went out on 4 October 1957.

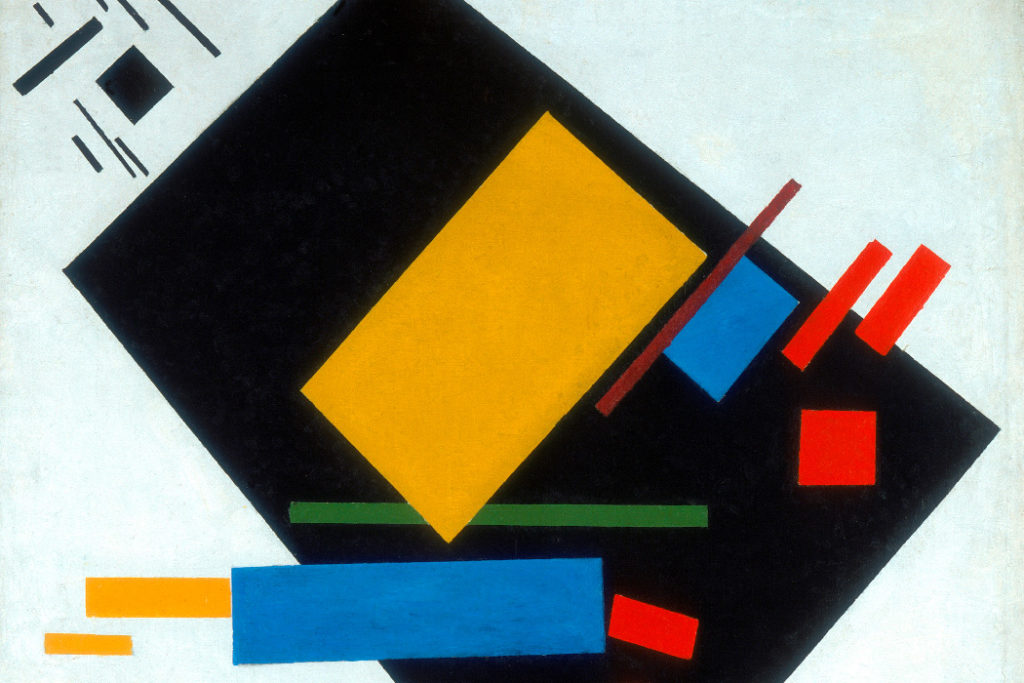

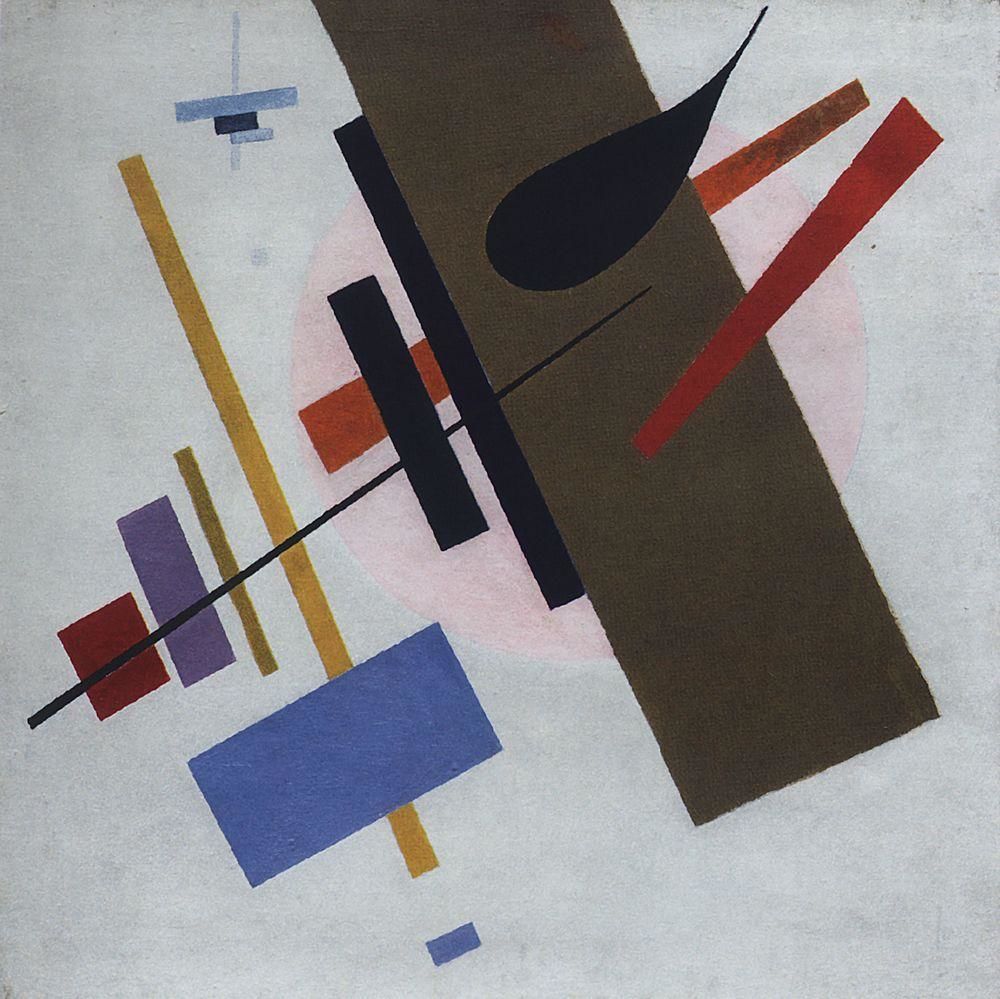

Supremus 58

In his text, Malevich lays out visionary ideas of amazing heuristic power, while touching on a sphere seemingly removed from art – technology:

The Suprematist machine, if it can be put that way, will be single-purposed and have no attachments. A bar alloyed with all the elements, like the earthly sphere, will bear the life of perfections, so that each constructed Suprematist body will be included in nature’s natural organisation and will form a new sputnik; it is merely a matter of finding the relationship between the two bodies racing in space. A new sputnik can be built between Earth and Moon, a Suprematist sputnik equipped with all the elements that moves in an orbit, forming its own new path.

In these last words one cannot help but recognise the space stations so familiar to us today, which truly are ‘new sputniks equipped with all the elements’.

Malevich goes on to propose a scheme for overcoming gravitation between celestial bodies and ensuring progressive advancement into the cosmos: ‘After studying the Suprematist shape in motion, we have decided that movement in a straight line towards any planet can only be accomplished by the annular movement of intermediate Suprematist sputniks forming a direct line of rings from sputnik to sputnik.’ Then come lines that make us think that the artist had peered into the distant future: ‘In my research I discovered that Suprematism holds the idea of a new machine, i.e. a new, wheel-, steam- and gasoline-less engine of the organism.’

For many years, Malevich the theoretician used astronomic terms while studying the culture of contemporaneity. Tools borrowed from the astronomic discourse seemed to bolster and strengthen the strict universal law that he believed served as the foundation for artistic creation. The great generator of plastic ideas labelled his architectural models, or architectons as they were called, with Greek letters the way astronomers label the constellations. His architectons (alpha, beta, zeta) were also the earthly precursors of a new architecture; they were supposed to be transformed into ‘planits’ – installations soaring into space and inhabited by ‘earthlings’. ‘Planits for earthlings’ were on a par with the planets and stars in the universe. The designs and neologisms Malevich created for them neatly accentuated Suprematism’s cosmic vector.

TEXT TAKEN FROM ‘THE COSMOS AND THE CANVAS – MALEVICH AT TATE MODERN’